Around 20% of the western world’s population live with a food intolerance or malabsorption syndrome [1], The British Nutrition Foundation defines a “Food Intolerance as a range of adverse responses to food, including allergic reactions resulting from enzyme deficiencies, pharmacological reactions and other non-defined responses”[2].

Many of the symptoms experienced by those suffering from a food intolerance are labelled by clinicians as IBS. Clinicians face huge challenges when diagnosing food intolerances when presented with a variety of very similar gastro- related symptoms, which can often also be typically classed as IBS. This has led to IBS being used as an umbrella term for gastro related complaints rather than individuals being diagnosed with more specific intolerances.

Vasoactive Amine Intolerance, more commonly known as Histamine Intolerance (HIT for short), is one of these chronic diseases which can be so often misdiagnosed by clinicians as IBS. Research into Vasoactive Amine Intolerances have shown that this type of intolerance may attribute itself for some of the misdiagnosed food intolerances of individuals, with around 1% of the world population suffering from HIT.[3]

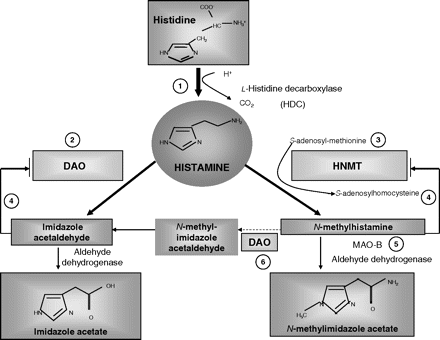

Histamine within the body is a signalling molecule which has a multitude of physiological functions. Histamine has key roles in cell growth, glucose metabolism, chemotaxis, and phagocytosis. Histamine itself is most associated with allergic reactions and inflammation. Histamine is synthesized in the body by the process of decarboxylation of the essential amino acid L-histidine, by an enzyme called histidine decarboxylase (HDC). [4] Histamine is stored in a variety of cells in the body, from mast cells, basophils, the gastric mucosa, and histaminergic neurons storing it in their intracellular granula. Small amounts of histamine have also been shown to be synthesized in lymphocytes and epithelial cells. [5] Figure 1, demonstrates how histidine is metabolised into histamine, in which it is broken down via two pathways using the enzyme diamine oxidase (DAO) and or histamine-N-methyltransferase (HNMT). The process in which histamine is degraded appears to depend on where in the body the histamine is located. Regarding HIT sufferers, the focus is mainly on the DAO degradation pathway due to the thought in the scientific community that DAO acts as a scavenger for extracellular histamine. DAO is also restricted to certain tissues within the body which are related to the gastro region.

Figure 1: Maintz, L. and Novak, N., 2007. Histamine and histamine intolerance. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, [online] 85(5), pp.1185-1196. Available at: <https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/85/5/1185/4633007>.

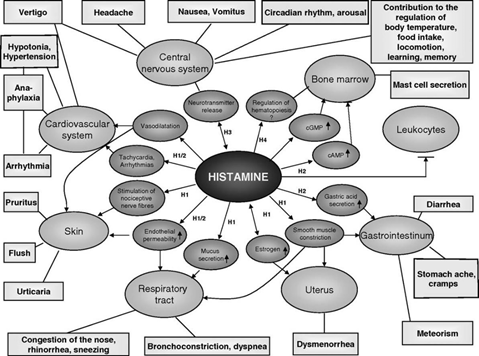

The reason why HIT is often so difficult to diagnose and could be misidentified as IBS is how the intolerances manifest themselves in the body, with the wide range of symptoms a patient could experience at once, or over several months. Figure 2 below gives a detailed diagram of all the potential symptoms which can be experienced by a HIT sufferer. [6]

Figure 2: Maintz, L. and Novak, N., 2007. Histamine and histamine intolerance. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, [online] 85(5), pp.1185-1196. Available at: <https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/85/5/1185/4633007>.

Histamine is most known for its association with hay fever sufferers and being a mediator in allergic reactions and anaphylactic shock. HIT as an intolerance is effectively the unbalancing of the accumulation of histamine in the body and its breakdown. There are a variety of different mechanisms in which an individual could develop a histamine intolerance. They range from consuming high levels of exogenous histamine either from the environment or from consuming high histamine containing foods, changes in an individual’s gut microflora population, leaky gut syndrome, GI bleeding, mastocytosis and the overuse of prescribed antibiotics without probiotics to counteract the effects.

As shown above in Figure 2, symptoms of HIT can be wide and varied, with individuals experiencing a wide range of symptoms sometimes all at once, other times at random, adding confusion for patients and clinicians as to the cause of the symptoms. Some of the most common symptoms can display themselves in the skin, including itching, recurrent eczema, swelling, hives and red flushed skin. GI symptoms often result in pain, cramps, bloating, diarrhoea, acid reflux etc. Patients have also noted, with undiagnosed HIT, respiratory symptoms such as streaming nose, persistent coughs, asthmatic related symptoms, tight chest, and difficulty in breathing during exercise. More severe, but not unusual symptoms can manifest in the nervous and cardiovascular system causing headaches, heart palpitations, increased blood pressure, anxiety, fainting and confusion. Chronic symptoms lead to systemic fatigue, painful periods in women, mental health complications, panic disorders, depression, and insomnia. [7]

Currently, the gold standard for diagnosing a histamine intolerance is not clear. It is recommended that at least two symptoms that are commonly associated with HIT are identified in the patient. The patient must then keep a record in a food diary of food consumed and symptoms experienced throughout the day/night. This allows for an investigation into the amount of histamine being ingested from exogenous sources and whether there is any correlation between foods consumed and symptoms experienced. A histamine food exclusion diet then follows to see whether symptoms improve on a low-histamine diet. As it is impossible to remove histamine completely from the body, clinicians must also rule out any other causes of symptoms such as actual food allergies through the skin prick test, as well as identifying any medication side effects that may be contributing to the patient’s symptoms. If symptoms improve within a month on a low histamine diet, then the likelihood is high that the individual has HIT. [8]

There are mixed opinions within the scientific community over what foods are histamine “releasing” or can antagonise a HIT sufferer’s symptoms. A low histamine diet is very restrictive, as many foods naturally contain levels of histamine, although some more than others. It is always recommended that patients agree to go on a low histamine diet with support from a registered dietician to ensure than the patient does not suffer from any malnutrition during the restricted diet phase. Due to the restrictiveness of the diet, it is not appropriate for a patient to be on this diet for their whole lifetime. Table 1: Histamine Releasing & High Histamine Foods List, details some foods and food groups which are backed by scientific evidence as being high in histamine or histamine releasing. It is, however, not an exhaustive list and histamine intolerance sufferers may have other foods which cause reactions and symptoms. Overall, these foods should not be consumed or consumed in significantly lower quantities during the low histamine diet phase.

Table 1: Histamine Releasing & High Histamine Foods List [9] [10]

| Food Groups | Histamine Containing Foods |

| Meat & Poultry | All cured meats (including bacon, salami, ham etc.) |

| Sausages | |

| All fresh pork products | |

| Aged steak/game | |

| Seafood | Tinned/Canned fish (including tuna, sardines, mackerel etc.) |

| Processed fish products, pates and spreads | |

| Fresh shellfish (such as: prawns, crab, lobster etc.) | |

| Milk & Eggs | All hard and ripened cheeses (such as: Stilton, Cheddar, Brie, Gouda etc.) |

| Soft cheese (such as: Goats' cheese, Mozzarella, Feta etc.) | |

| Cooked/raw eggs (such as: scrambled, poached and fried etc.) | |

| Yoghurts and fermented yoghurt products (such as: buttermilk, sour cream, kefir) | |

| Fruits | Bananas |

| Tinned fruit (especially tinned figs) | |

| Citrus fruits (including grapefruits) | |

| Pineapple | |

| Grapes | |

| Strawberries | |

| Dried fruits containing preservatives such as sulphites | |

| Vegetables | Aubergine |

| Spinach | |

| Avocados | |

| Fermented or pickled vegetable products (such as: sauerkraut) | |

| Tomato and tomato-based products (such as: tomato sauces, ketchup, chutneys etc.) | |

| Olives | |

| Legumes/pulses | |

| Nuts | Tree nuts (such as: hazelnuts, brazil nuts, pecans, cashews etc.) |

| Peanuts | |

| Cereal & Grains | Sourdough bread |

| Yeast | |

| Marmite | |

| Condiments & Miscellaneous | Fermented soya products (such as: soya sauce, fish sauce, miso etc.) |

| Vinegar | |

| Pickles | |

| Dressings containing vinegar | |

| Chocolate (dark, white and milk) | |

| Drinks | Coffee |

| Hot chocolate | |

| Tea/Green tea | |

| White, rose and red wine | |

| Champagne and Prosecco | |

| Beer and cider | |

| Fruit juices/smoothies made from above fruits |

Table 1 clearly indicates why it is near impossible to maintain a low histamine diet in the long term due to the vast amount of foods that would require avoidance, likely to ultimately result in malnutrition. It can be noted within the food list that microbial fermentable foods such as wine, cheese, cured meats have an antagonising effect on HIT symptoms due to certain gut bacteria’s species producing histamine from these foods and their organic biproduct compounds.

Gut health has often been associated with being a cause of HIT in some individuals. M Schink & P. C Konturek in 2018 studied the microbial patterns of patients with histamine intolerance to see whether these individual’s gut microflora differed to that of healthy individuals. In particular, they focused on whether the species of bacteria colonising the individual’s guts could be contributing to their histamine intolerance and symptoms. The study concluded that gut health has a huge impact on immune functionality in the host and that bacteria-based metabolites produced in the gut can have an immense effect on human health. The study highlighted that certain strains of bacteria have histidine decarboxylase enzyme inhibiting properties, which would reduce the degradation of histamine to histidine in the body. Equally, there appeared to be an imbalance of families of bacteria in the gut of the HIT sufferers, with higher levels of Proteobacteria identified. Proteobacteria are often seen as a sign of gut dysbiosis and can cause gut inflammation affecting the epithelial layer in the gut. The increase of Proteobacteria also causes heightened levels of oxygen in the colon, which leads to the promotion of facultative anaerobic bacteria, unbalancing the amount of Bifidobacterial species in the gut. Bifidobacteria are often associated with good gut health. It is considered that inflammation in the gut leads to the disruption of mature epithelial cells, which host the DAO enzyme and help to degrade exogenous histamine levels. A dysbiosis of species of gut bacteria and cells of the gut could lead to an increase of endogenous histamine levels. [11]

So, are you stuck with a histamine intolerance for life? Due to this being a relatively new area of research, with many clinicians still not knowing what HIT is and being unable to identify it in their patients, there is no real consensus on the long-term prognosis. Whether a patient can be completely cured of their HIT symptoms, or whether it is something that patients will have to manage on an individual basis for the rest of their lives remains to be seen.

There is, however, hope for HIT sufferers as currently, research has shown that a multi-pronged approach to tackling HIT can be effective in managing symptoms long term. These include identifying trigger foods, adhering to a low histamine diet, managing stress levels through yoga or meditation, supplementation for certain vitamins and minerals, and finally taking a histamine friendly probiotic. Although it is not advised for patients to adhere to a restricted histamine diet forever due to the risk of malnutrition, a study by Lackner S, Malcher V and colleagues showed that applying and adhering to a low histamine diet just occasionally or during a “flare-up” of symptoms could help to increase the levels of DAO enzyme and reduce symptoms, having an overall positive effect on the patient’s health.

As mentioned previously, a decrease in the level of the DAO enzyme appears to be a trigger for why people suffer from HIT. A dysbiosis in the gut epithelial cells can damage the effectiveness of DAO production, creating a circular link of decreasing DAO levels and exacerbated symptoms.[12] Several research studies have also shown an improvement in symptoms from taking DAO enzyme supplements. These supplements are now commercially available for patients to access and consist of a preparation of pig’s kidney, which has a high concentration of DAO enzyme. It is thought that the exogenous DAO breaks down histamine present in the gut from exogenous sources such as food, lowering the build-up of histamine. However, more research is required into the benefits of taking DAO supplements and their true biological process within the gut. [13]

Current advice on helping HIT sufferers is a multifaceted approach, from low histamine diets to the use of probiotics to help improve gut diversity and reduce gut inflammation, along with the use of antihistamines. There is also interest around vitamin co-factors which aid the DAO enzyme in degrading histamine, such as the B complex vitamins. Vitamin B6 and Vitamin C, in particular, have been shown to reduce symptoms of seasickness and histamine intolerance. The full benefits of Vitamin C and Vitamin B6 on HIT sufferers are still not fully understood. However, some studies have indicated that they may have a therapeutic effect, perhaps due to aiding the DAO enzyme, even increasing the levels naturally in the body. Jarish R and colleagues, who were investigating the therapeutic effects of Vitamin C supplementation on sufferers of seasickness, identified the correlations between seasickness and histamine intolerance symptoms. They also noted throughout their study that individuals who received the Vitamin C supplementation saw an increase in DAO levels and a decrease in seasickness symptoms. There was also an interesting reference to the Samoan populations, who traditionally would eat 1-2 mangos before travelling by sea in boats to prevent seasickness symptoms. Mangos have the equivalent amount of vitamin C in them to many other citrus fruits, such as oranges and lemons. Mangos are also classed as a fruit suitable for a low histamine diet, unlike oranges and other citrus fruits. Therefore, this may be an interesting avenue for research on the therapeutic use of mangos, either incorporating them into the diet of a HIT sufferer or supplementation of Vitamin C sourced from mangos. [14]

Many Histamine Intolerance sufferers mention a feeling of isolation or desperation, especially when facing clinical staff who can neither understand nor interpret symptoms and how they affect an individual’s daily life. Histamine attacks can be persistent and highly unpleasant, and cause a constant fear for some individuals. A lot more research in this area is required to find the underlying causes of HIT and how individuals can be helped to manage their symptoms and diet. Equally, more training is needed for healthcare and clinical professionals to have a deeper understanding of this intolerance, to ensure that more people will have a chance of a meaningful diagnosis and often not require prescriptive drugs or medication. The answers may be a long way off yet, but HIT sufferers are now being listened to, and research in this area is progressing steadily.

RELATED POSTS:

References

[1] Schnedl, W., Lackner, S., Enko, D., Schenk, M., Holasek, S. and Mangge, H., 2019. Evaluation of symptoms and symptom combinations in histamine intolerance. Intestinal Research, [online] 17(3), pp.427-433. Available at: <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6667364/>.

[2] The British Nutrition Foundation. 2020. What Is Food Allergy And Intolerance?. [online] Available at: <https://www.nutrition.org.uk/nutritionscience/allergy/what-is-food-allergy-and-intolerance.html?__cf_chl_jschl_tk__=a61bef59e77652146ecc90485103fe7d3146f1a9-1590502565-0-AZPtnaQMpMYhePblBJQFIlWIHHwf1w-f3yK9wH6cGsyMTUjNMdYT1jYSgzsI6YDaaUNY9RSurK0r3AOzQ8v1f-Zg62I92Dcp1hISZ4ruhjx9-BJF9ldLEaEAoeog5tlsrbIb44uZYRQ9TTMFwRbR18oNH9JToMoUpoFaQbYrztvnvDj_ThSqPFpYVwCmkqB-jesAVai7Uq6l-fAC5mAs_YayKet2GaDguOyzNXJHySX_gNroNqfclE7XVYA6j8MqMneGpOZqo2m-0YO3oDHC05vYnTG_zqdh9TsB3uIwfCZBU-9tdiU6pzi9j-YfjAkm_BMNpBnLxXRycBf1xg6nY35fymsYRgzvqQ4FPvY1n4zXMBJYZaa8fG4GlsEPuYiiluMjq6xHnQxCE9p4hKqm8MGwLyZbr2-hwE55CJOVP8mQ> [Accessed 26 May 2020].

[3] Maintz, L. and Novak, N., 2007. Histamine and histamine intolerance. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, [online] 85(5), pp.1185-1196. Available at: <https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/85/5/1185/4633007>.

[4] Luttrell M, Halliwill J. The Intriguing Role of Histamine in Exercise Responses. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews. 2017;45(1):16-23.

[5] Hattori Y, Seifert R. Histamine and Histamine Receptors in Health and Disease. Springer; 2017.

[6] Maintz, L. and Novak, N., 2007. Histamine and histamine intolerance. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, [online] 85(5), pp.1185-1196. Available at: <https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/85/5/1185/4633007>.

[7] Kovacova-Hanuskova, E., Buday, T., Gavliakova, S. and Plevkova, J., 2015. Histamine, histamine intoxication and intolerance. Allergologia et Immunopathologia, [online] 43(5), pp.498-506. Available at: <http://file:///C:/Users/joanna/Downloads/Kovacova-Hanuskovaetal.-2015-Histaminehistamineintoxicationandintolerance.pdf>.

[8] Kovacova-Hanuskova, E., Buday, T., Gavliakova, S. and Plevkova, J., 2015. Histamine, histamine intoxication and intolerance. Allergologia et Immunopathologia, [online] 43(5), pp.498-506. Available at: <http://file:///C:/Users/joanna/Downloads/Kovacova-Hanuskovaetal.-2015-Histaminehistamineintoxicationandintolerance.pdf>.

[9] Draft guidance from the British dietetic association on Vasoactive Amine Intolerances

[10] Maintz L, Novak N. Histamine and histamine intolerance. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition [Internet]. 2007;85(5):1185-1196. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/85/5/1185/4633007

[11] Schink M, Konturek PC, Tietz E, et al. Microbial patterns in patients with histamine intolerance. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2018;69(4):10.26402/jpp.2018.4.09. doi:10.26402/jpp.2018.4.09

[12] Lackner S, Malcher V, Enko D, Mangge H, Holasek S, Schnedl W. Histamine-reduced diet and increase of serum diamine oxidase correlating to diet compliance in histamine intolerance. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition [Internet]. 2018 [cited 4 December 2020];73(1):102-104. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41430-018-0260-5

[13] Schnedl W, Schenk M, Lackner S, Enko D, Mangge H, Forster F. Diamine oxidase supplementation improves symptoms in patients with histamine intolerance. Food Science and Biotechnology [Internet]. 2019 [cited 4 June 2020];28(6):1779-1784. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10068-019-00627-3

[14] Jarisch R, Weyer D, Ehlert E, Koch C, Pinkowski E, Jung P et al. Impact of oral vitamin C on histamine levels and seasickness. Journal of Vestibular Research [Internet]. 2014 [cited 9 June 2020];24(4):281-288. Available from: https://content.iospress.com/download/journal-of-vestibular-research/ves00509?id=journal-of-vestibular-research%2Fves00509#:~:text=CONCLUSIONS%3A%20Some%20of%20the%20data,had%20been%20exposed%20to%20waves.

Photo by JOSHUA COLEMAN on Unsplash.