Start your free trial

Arrange a trial for your organisation and discover why FSTA is the leading database for reliable research on the sciences of food and health.

Arrange a trial for your organisation and discover why FSTA is the leading database for reliable research on the sciences of food and health.

One of the best things about the training sessions and webinars we deliver is the questions we receive.

These questions have inspired some of your and our favourite content, so we wanted to make it even easier for you to ask us a question and to see what other people have been asking us.

Enter your question above and we will respond to you directly by email. If we think other people would find the question and answer useful, we may share it here and on our other channels, such as social media. This will not include any identifying information about you, of course.

Searching for scientific research can mean trawling through vast numbers of articles and other sources in order to locate the most relevant results. The best searches are ones that strike the right balance between being broad enough to ensure you don’t miss relevant research, but specific enough to avoid what is irrelevant. We have brought together a range of practical tips that you can use to ensure your search is as effective as possible.

The three main Boolean operators are AND, OR, and NOT. Each instructs a database how search terms need to be combined, and that lets us configure searches to find more precise and relevant results. View and download our tips for effective searching or learn more.

Yes! The filter is specific to the platform you are searching FSTA on, so we have a selection of resources available based on the platform you use to access FSTA:

EBSCOHost

Ovid

Web of Science

While most academic research in food and nutrition science is published in scholarly journals, research conducted in industry might be shared with the world only when its intellectual property can be protected, through patents. University researchers also sometimes patent methods and technologies. Patent documents are sometimes the only way for researchers to get access to this information. Learn more

Once you have the title of a patent, you can usually find its full text if you type it, inside quotation marks, on the free websites Espacenet or Google Patents. Learn more about finding patents and getting their full text.

Phrase searching means typing two or more words - words that, used together, capture a concept - inside quotation marks in a search. It can be very useful for narrowing a search if the phrase you are using is really a phrase, but if your words do not need to be a phrase you will miss relevant results. Learn more

You can also watch our on-demand webinars on how to use phrase and proximity searching on EBSCOhost, Ovid, or Web of Science.

The phrase adjacency searching is often used synonymously with proximity searching. This kind of search uses a proximity operator to stipulate that search terms be no more than a stated number of words from each other in a field, like the title or abstract, of a record. Learn more

You can also watch our on-demand webinars on how to use phrase and proximity searching on EBSCOhost, Ovid, or Web of Science.

Proximity searching lets you determine how close one search term must be to another in order for the results to be useful for you. You do this by inserting a proximity operator between your search terms. Learn more about this kind of searching and how useful it can be here.

You can also watch our on-demand webinars on how to use phrase and proximity searching on EBSCOhost, Ovid, or Web of Science.

Proximity operators are what you type between your search terms to run a proximity search. Exactly what you type is platform dependent. What they all have in common, though, is that they let you include a number to indicate the maximum distance the search terms can be separated from each other. Find what a platform's operator is in its help section. Learn more about proximity operators and how to use them.

You can also watch our on-demand webinars on how to use phrase and proximity searching on EBSCOhost, Ovid, or Web of Science.

Stopwords are words that are not counted as words for a database’s search rules. They are usually common words like and, as, for, from, is, of, that, the, this, to, was, and were. Find out more

You can also watch our on-demand webinars on how to use phrase and proximity searching on EBSCOhost, Ovid, or Web of Science.

A peer reviewed journal article has been read and approved for publication by experts in the field.

As a student researcher who is building knowledge but is not yet an expert, it gives you the reassurance that the article you are reading is based on solid research, though there still may be arguments over its conclusions, and it still needs to be critically appraised. The process works like this:

The most common forms of peer review involve keeping identities of reviewers and/or authors secret, at least until the peer review process is over. These are known as Single Blind (where the author does not know the names of the reviewers), and Double Blind (where all author information is removed from a paper, and neither reviewers or authors can be identified). Learn more about peer review from an author's perspective.

We have a range of resources available, such as downloadable guides, videos and more, depending on the platform you use to access FSTA. Take a look at our training hubs for EBSCOhost, Ovid and Web of Science.

Some databases tag their records with controlled vocabulary terms to help researchers find the exact results they need. Tagging records from a specific, discipline-based list of terms is called indexing.

To understand indexing, it can be helpful to think of it as a two-part process. First, subject experts compile (and keep updating) the subject-based controlled vocabulary list. Not only does this list contain all the important and nuanced terms for the discipline, but it also pulls together the different versions of terms researchers from around the world use to describe the same concept. The second part is the indexing itself, where an indexer assigns the appropriate terms from the list to each database record to capture what that piece of research is about. This two-part process helps researchers find the research they need.

Comparing how searching and finding results works in an academic search engine (Google Scholar) with how it works with an indexed database (FSTA) really shows how indexing works, and how helpful it is.

When searching Google Scholar you will only get results that include exactly what you type in the search box. If you type flavour, you will get one set of results. You’ll get a different set if you type flavor. You’ll get different results again for flavours and for flavors. And the search engine will definitely not search for results containing flavour synonyms like taste, or tastes, or tasting, or translations of flavour into different languages.

In contrast, if we search FSTA for flavour, our results include the variations, plurals and synonyms. This is all thanks to the thesaurus underpinning our search. In fact, with a single search for flavour in FSTA, we get results in 40 languages, pulled together for you. You don’t need to figure out the 40+ versions of the word you would have to search in Google Scholar. This is the power of indexing.

Plus, the titles and abstracts of each of these records will be available in English, allowing you to make an educated judgement about whether you actually need the full text.

You can find out more by watching this short video

Google Scholar is the most popular search engine used by those looking for scholarly content, but there are significant limitations to its effectiveness.

In comparison to FSTA, Google Scholar is an inferior search tool that produces a large number of irrelevant search results, whilst missing relevant results. It also includes fake and inadequate science.

FSTA avoids all of these problems by employing a team of food scientists to

Dr Helena Korjonen, University of Luxembourg, carried out a review of the literature to find the potential issues that using Google Scholar can bring. Read more

Google Scholar and FSTA work very differently in how they find results. Google Scholar searches for exactly the word or words that you type, while FSTA is built on a thesaurus of controlled vocabulary.

Learn about why this makes a difference when you are searching for information by reading this article or watching this short video.

When you need to answer a question, it helps to imagine what kind of source is likely to give you a good (accurate) answer, and where you can find that kind of source. In this section of Ask an Expert, we list factual questions people have submitted to us, and give tips on what to think about in searching for the answers. It’s all about successfully navigating today’s vast and complicated information landscape.

Here, we will cover some of the things to consider when seeking an answer to a question like this.

“Is milk healthy?” is a broad question. That breadth makes it hard to find a definite answer. Healthy for who? Kids? Post-menopausal women? Lactose intolerant people? How much milk are we talking about? A little or a lot? And what kind? Skim? Full fat? Organic? By breaking down the question, we are starting to think about the variable controls that might be put on the experiments that could answer it.

If we google “is milk healthy” we’ll get answers, but are the answers on websites accurate? What’s their evidence?

A better approach for finding an answer is to look for scientific literature investigating our question. But with such a broad question, the scientific literature is going to be overwhelming. How will we know which study to choose?

A solution to this problem is to search specifically for systematic reviews. Systematic reviews are scientific studies that locate all the published research that has been done on a particular question, as well as, sometimes, research that has been conducted but not published. The systematic review authors synthesize the data from the individual studies to see what overall conclusion can be drawn about their question. In a way, it’s as though they are pulling all the little—and sometimes not so little—studies together into a giant study for us.

Where you search will depend on what resources you have available to you—you’ll have more options if you are affiliated with a university than if you are not. Regardless, you’ll want to use a reputable subject appropriate database that indexes research articles. Why? A database like FSTA ensures that a first level of quality screening has been done for you—the articles you’ll find should be from a legitimate, peer reviewed journals, having gone through the review steps required for publication.

A quick, but not comprehensive, way to search for systematic reviews is to type the topic you are interested in (in this case milk and health) and then the phrase “systematic review.”

When we search for these systematic reviews, most, as expected, concentrate on specific health issues like milk and heart conditions, or milk and different cancers, or milk and bone health.

But in this case, there is also a recent umbrella review of systematic reviews looking at milk and a whole series of medical conditions. An umbrella review pulls many different reviews together into a single review, though it doesn’t synthesize the evidence the way a systematic review does. In this umbrella review, the researchers pulled together systematic reviews each looking at milk and a separate health problem to try to answer the broad question “is milk healthy?”

The authors of Milk consumption and multiple health outcomes: umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses in humans found that, “Milk consumption was more often related to benefits than harm to a sequence of health-related outcomes. Dose–response analyses indicated that an increment of 200 ml (approximately 1 cup) milk intake per day was associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular disease, stroke, hypertension, colorectal cancer, metabolic syndrome, obesity and osteoporosis. Beneficial associations were also found for type 2 diabetes mellitus and Alzheimer’s disease.”

But at the same time, the authors noted that “milk intake might be associated with higher risk of prostate cancer, Parkinson’s disease, acne and Fe-deficiency anaemia in infancy.” They also point out that many people are allergic to milk or are lactose intolerant.

Their conclusion overall was that “milk consumption does more good than harm for human health.”

Once you find a review answering your question, it’s important to consider its potential shortcomings. Unfortunately, even with peer review, some articles calling themselves systematic reviews don’t adhere to the standards and steps needed to make their conclusions entirely trustworthy. Bias can be introduced into other kinds of studies, too. A critical appraisal checklist can guide you through the questions you should ask to assess a research article’s quality.

You should also pay attention to the limitations that the authors themselves point out. In our milk and health article, the authors state that “more well-designed randomized controlled trials are warranted.” This tells us that some of the systematic reviews they gathered in their review had based conclusions on studies that aren’t the very best kind for coming up with definitive answers on health questions. When more studies are done in the future, the scientific consensus on milk’s health benefits might shift.

Finally, it’s worth noting that the umbrella review about milk consumption and health outcomes does not address the impact milk production has on climate change, and the implications climate change has for global human health. There is scientific literature looking at that, too. It’s always worth considering the different ways you can frame your question—changing the frame might change the answer.

To find a good answer to this question, we will want to think about three things:

This question is asking about how to perform an established mathematical process. It is not the kind of information that would be found in research articles. Instead, it would be found in teaching materials. A clear and accurate answer could come from a textbook or from another teaching resource.

If you have an appropriate textbook, check its table of contents at the front or index at the back to find where in the book you’ll find what you need. Alternatively, lots of high-quality teaching materials, including videos, are freely available online. To find these, search the internet using any general search engine like Google, Ecosia, or DuckDuckGo.

When I searched, my results included some specifically related to chemistry. Assuming that a more basic explanation is what we’re after, though, two options stand out. One is a short series of videos from Khan Academy: Intro to significant figures (video) | Khan Academy. The other is a PDF from the Yale Department of Astronomy: SigFig.pdf (yale.edu)

While it seems unlikely that anyone would bother to post online a deliberately wrong answer to this question, sources will be better or worse at explaining the concept to someone who doesn’t already understand it. Thinking about the reputational quality of sources is always helpful for making a good selection amongst a long list of options.

Khan Academy is a well-established, non-profit online teaching academy dedicated to producing high quality teaching materials that anybody can access. How do I know this? A search for Khan Academy surfaced this information from a number of sources beyond the Khan Academy webpages. Always look not just at information that an organization provides about itself, but also at information you can find about it from other sources. Remember—a substandard organization would not advertise flaws or controversies in its own webpage “about” information.

Yale, a top world university, doesn’t need to be double-checked for quality. But a quick check does confirm that the PDF really is from Yale—shortening the full web address from http://www.astro.yale.edu/astro120/SigFig.pdf to http://www.astro.yale.edu takes you to the Yale Department of Astronomy webpage.

After checking these sources, I trust that both know what they are talking about. Both also—as you would expect from reputable teaching organisations—clearly explain and demonstrate the concepts needed to answer the question.

Along with the guidance provided in this section, you can also access our full Best Practice for Literature Searching Guide on Libguides, by free download, or through our free SCORM package for librarians or lecturers to to include in their learning management system (LMS).

Literature searching is the task of finding relevant information on a topic from the available research literature. Literature searches range from short fact-finding missions to comprehensive and lengthy funded systematic reviews. Or, you may want to establish through a literature review that no one has already done the research you are conducting. If so, a comprehensive search is essential to be sure that this is true.

Whatever the scale, the aim of literature searches is to gain knowledge and aid decision-making. They are embedded in the scientific discovery process. Literature searching is a vital component of what is called "evidence-based practice", where decisions are based on the best available evidence. Learn more

A literature review is a critical assessment of the literature relating to a particular topic or subject. It aims to be systematic, comprehensive and reproducible. The goal is to identify, evaluate and synthesise the existing body of evidence that has been produced by other researchers with as little bias as possible. Learn more about what is involved in a literature review.

Good searching takes place in three broad stages: planning, searching, and follow up.

In the planning stage, you line up tools to optimize organization and think about where you can and should search. You also begin to define your search question and translate it into a search strategy. This merges into the search stage, where you will try out your search strategy in different databases and refine, refine, refine! You will collect records along the way, but you don't need to get the full text of these articles until you start the follow-up stage where you screen the records, first cursorily, then carefully.

Following this procedure for your searching helps ensure that you are actually catching the research most relevant to your question. Learn more

Critical appraisal is the process of systematically evaluating and assessing the research you have found in order to determine its quality and validity. Critical appraisal is essential to evidence based practice. Learn more

The Academic Phrasebank (J. Morley, University of Manchester) is a useful resource for academic writing and is freely available here. It’s not specific to literature reviews, but will definitely be helpful.

For more information about systematic reviews, take a look at our practical guide. It takes you through the steps of carrying out a systematic review, including advice on how to follow standard methodology practices, key tools to use, and much more.

A systematic review is a type of research study where all the studies that have been done on a question to date are located and analysed to find a comprehensive answer to the question. A systematic review must capture all the relevant literature on a question so that its conclusion is based on all available evidence.

Systematic reviews are a structured, rigorous, and transparent form of literature evaluation that was first developed for evidence synthesis in clinical research. Its intention was to give policy makers and practitioners access to current state on evidence and help answering various health concerning questions. The increased credibility and transparency of the systematic review methodology gained popularity over time in other science domains including social care and environmental management.

In the last two decades, it has been accepted as the highest standard method of knowledge assessment across various research fields. It is now adapted by various healthcare organisations as well as governmental bodies and research institutes across more scientific disciplines to further research and to help translate relevant knowledge into various policies, guidelines, and practices.

For more information on systematic reviews, take a look at our complete guide - Good review practice: a researcher guide to systematic review methodology in the sciences of food and health

Systematic reviews are powerful tools for answering focused research questions. Focused questions that are specified sufficiently and contain all necessary elements similar to typical experimental studies are suitable questions. These are known as closed-framed questions. You can find examples of open and closed framed questions here.

Once you have determined your research question, it is important to check the intended SR topic for currency and novelty before conducting a systematic review to reduce the risk of conducting a redundant review.

The next consideration is the availability of the evidence and resources required to carry out the systematic review. Once you know you have a research question that is valid, it is important to identify all sources of information and weigh the quality and quantity of the evidence against the objective(s) of the intended review. In order to do this, you must secure access to the most relevant databases for comprehensive literature searching. Also, planning to use an appropriate reference management tool is critical for recording and managing references from the beginning of the project. The cost of subscription to relevant databases and reference management tools should be considered in budget planning.

It is also important to identify people with appropriate knowledge and skills to consult their views accordingly. These might include funders, commissioners, stakeholders, consumers, advisory board members as well as librarians, information specialists and data statisticians. Considering potential parties and stakeholders to carry out the work in collaboration is useful when resources (time or budget) are limited. Find out more

A systematic review is carried out in core steps, as outlined in this graphic.

The first and most important step in conducting a systematic review is framing the research question. The aim of this process is to break down the research question/issue into its main components or “key elements”. The key elements specify relevant concepts of a topic and set the boundaries for the study.

The literature search lays the foundation of evidence for a systematic review. A weak search degrades and potentially invalidates a review’s value. An information professional or librarian with systematic review experience should be a part of the systematic review team if possible. If not possible, training and consultation with such a professional should be sought to ensure that the searching step of a review is competent.

Three principles shape a systematic review’s search. The search must be systematic, comprehensive, and reproducible.

This step of the process is to screen and select relevant studies after searching is completed. Often it involves screening a large volume of studies and extracting appropriate data from them for inclusion in the review. The inclusion and exclusion criteria, the screening procedure and data extraction details are planned in the review protocol to guide this step.

This step of the process is to evaluate the quality of included studies and the overall strength of the evidence. Full texts of the included studies are required for the quality assessment process.

After the quality assessment is completed, the data is extracted from the included studies to make a conclusion about the outcome.

Data synthesis includes synthesising the findings of primary studies and when possible or appropriate some forms of statistical analysis of numerical data. Synthesis methods vary depending on the nature of the evidence (e.g., quantitative, qualitative, or mixed), the aim of the review and the study types and designs. Reviewers have to decide and preselect a method of analysis based on the review question at the protocol development stage.

The findings used to report on a systematic review include statistical analysis, discussion, conclusion, supplementary materials, and minimum requirements and editorial limits.

By going through these steps, a systematic review provides a broad evidence base on which to make decisions about medical interventions, regulatory policy, safety, or whatever question is analysed.

More information about each step of this process is available in our researcher guide to systematic review methodology

The best place to register your systematic review protocol depends on the discipline it falls within. Find a list of options for the sciences of food and health here

Most systematic reviews are quantitative. Systematic reviews can also be qualitative, but these follow a different method and answer different question types than a quantitative review does.

When a review is just called a systematic review, the assumption is usually that it is synthesizing quantitative evidence. A qualitative review can be called a qualitative evidence synthesis (the preferred term), a qualitative systematic review, a qualitative research synthesis, or a qualitative meta-synthesis.

For a good overview, as well as links to further information, about qualitative evidence syntheses, see Flemming, K., & Noyes, J. (2021). Qualitative Evidence Synthesis: Where Are We at? International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20.

Find more information about quantitative reviews in our researcher guide to systematic review methodology

Predatory journals are a deceptive, money-making practice by unscrupulous publishers. Whether you are trying to find trustworthy research, or somewhere to publish your work, identifying and avoiding predatory publishers is essential. You can find more information in our Predatory Journals Hub.

Basically, a predatory journal is one that is published by an unscrupulous publisher in order to make money without providing the services you would expect from a genuine journal, such as proper peer review and editing services.

Predatory journals will typically publish any, or almost any, research article with few or no quality checks, so the literature published in them is unreliable, and sometimes completely fake.

There are several different terms used to describe these journals and publishing operations, and different ways in which the key problems with them can manifest. Other terms often used to describe these practices include ‘fake’, ‘deceptive’ and ‘shell’.

There’re no definitive criteria for what makes a journal "predatory", but areas such as intention, impact, monetary gain, quality, status, and reputation are all factors in how they can be assessed. Learn more

As a reader, you want to be sure that what you are reading is a legitimate source of scientific information. It can be surprisingly easy to come across articles from predatory journals when researching, particularly on resources like Google Scholar.

Because the journals exist with the sole intention of making money, it has enabled research of questionable quality (that would not likely have been published in other, better quality journals), to be made available on the internet for any unwary reader to find.

Once the research is available in the academic ecosystem, it can be cited and work its way into subsequent articles. This has a negative impact on future research and risks its scientific integrity.

Thankfully, there are ways to avoid predatory publishing. For example, using databases with quality management processes and human curation, rather than search tools which automatically index anything that looks relevant. Our strict quality control measures mean that you can be confident that there is no content from predatory sources in FSTA.

Learn more about how to avoid predatory journals when researching.

Even if your research is of a high quality, being associated with a questionable journal is likely to limit its reach.

Predatory journals are designed to take financial advantage of researchers, notably young doctoral students who are under pressure to publish articles towards PhD and post-graduate assessments. They abuse the Article Processing Charge (APC)-based open access model, publishing papers without the expected editorial scrutiny and providing an easily accessible venue for publication that often guarantees acceptance, to meet this demand. These operations undermine the integrity of open access publishing as a whole.

If your research is published in a predatory journal, it is likely to be disregarded by other researchers who are avoiding these publishers. It is also less likely to be indexed in databases with strict quality control measures, such as FSTA, making it harder for researchers to find and read your paper.

Take a look at our Guide to Publishing in Journals for step-by-step advice on the whole publishing process.

There are resources which may confirm that a journal is predatory, but it’s also important to be aware of possible warning signs to look out for.

There used to be a publicly available list called Beall’s List. It is no longer active, though archived versions can be found online. Cabell’s Scholarly Analytics have a Predatory Journals Report service including a searchable database.

You should equip yourself with an understanding of what predatory publishing is and common characteristics of predatory journals. This can help you assess a journal or publisher you come across. On its own, just one feature may not be sufficient cause for concern, but several together may be an indicator.

In addition, you can check that a journal is reliable rather than whether it is predatory. We have tools and resources that help with that.

First, familiarise yourself with the search platform you are using. Do they have inclusion criteria and quality assessment processes for content?

For example, to be included in FSTA, journals must meet a quality threshold based on the criteria covered by our 60-point checklist. Any journal not meeting our quality standards and suspected of using predatory/unethical practices will not be included in FSTA. So, when searching in FSTA, you can be confident that the results you find are not from predatory sources.

You can also check that a journal is credible by using our free Journal Look Up Service (JLS). You can quickly and easily check if we index a journal in FSTA so you can be confident it is peer-reviewed and not predatory.

Predatory journals usually use deception and misinformation. Some of the common forms this takes are:

In isolation, any of these individual features may not be sufficient cause for concern, but several together may begin to raise warning flags for you and you should probably investigate more closely.

More details can be found in our Predatory Journals Hub.

We cannot provide a definitive list of predatory publishers, but thanks to our assessment procedure, when you search in FSTA you can be confident that your results will not include any predatory content. With our Journal Look Up Service (JLS), you can check if we index a journal in FSTA and verify it is not predatory.

There are also ways that you can assess a journal or publisher. Take a look at the questions above or at our Predatory Journals Hub for more information on how to identify predatory journals.

In addition to ensuring new journals include sufficient content within the scope of FSTA’s subject area coverage, our editorial team of experts in the sciences of food and health conduct a thorough evaluation of each new journal against a checklist of criteria relating to potentially predatory or unethical publishing practices. This enables us to identify and exclude publishers and journals that may be using such practices. Our checklist covers 60 measures across several diverse areas. Learn more

Publishing research and scholarly work in a highly regarded credible journal is a key part of academic careers, but the process can be daunting to those new to it. is something that many find to be incredibly challenging. Below are some of the key answers you may find useful. For a more in-depth look, take a look at our Guide to Getting Published in Journals.

Although it is very easy to self-publish your own work through a range of platforms such as websites, blogs, and social media accounts, publishing research and scholarly work in a highly regarded journal is a key part of academic careers. There are several key benefits to publishing research in journals including discoverability, contributing to the records of research in the field, the benefits of peer review, dissemination and impact, career advancement and preventing duplication of effort. Learn more

Our Publishing Guide has been developed to help authors navigate the process of selecting appropriate journals and understand the range of factors which might influence the decisions of where to submit. The guide explains a range of topics including the benefits of publishing in journals, different open access models, publishing ethics, and more.

The Aims and Scope of a journal provides the key information about it - why it exists, what it aims to achieve, and what it is looking for from submissions. This information can usually be found on the journal website.

Understanding the Aims and Scope of a journal is critical to getting past the first hurdle of editorial review, and on to the peer review process. Failure to properly fit the subject scope of the journal or to help it further its editorial aims are common reasons for immediate rejection of submissions. It is important to make sure that you clearly understand it by investigating the journal website and reading sample articles, especially from recent issues. Key information to look for includes statements about subject or geographic scope, readership, and novelty or contributions. Make notes of all these aspects for each of your journals of interest.

For the paper you are currently writing, or looking to submit, consider how well your methods, sample populations and conclusions relate to the aims, scopes and readership of a journal, to understand whether it is suitable. Learn more

Citation metrics are an average of citations received by a journal, within a particular time frame. These can give us some helpful insights into the standards and history of journals, and may be an important factor in deciding where to submit your paper.

It may be assumed that a high citation metric has editorial processes of a high standard, but what it really means is that a journal is receiving a lot of citations and may be worth investigating further. The metrics themselves can be subject to a great degree of change. Just one highly cited paper can make a significant difference to the metrics of a journal year-on-year, so looking at a single metric for one year is not enough to determine the overall stature of a journal. By looking into their citation profile and metrics over the previous years you will get a better idea of the consistency of how a journal is used by the field.

It is worth noting that the use of citation metrics as a method for assessing the quality or value of research, journals, and especially individual researchers, has been a fiercely debated, controversial issue. Learn more

Alternative metrics, or altmetrics, monitor attention to individual articles and research outputs, providing almost instantaneous updates on the mentions of papers from a wide range of sources. These include traditional citations, public policy documents, mainstream media newspapers, blogs and websites, online reference managers, post publication review sites, Wikipedia, and social media platforms.

While traditional citation metrics are calculated by assessing the average number of citations received by a journal within a particular timeframe, altmetrics can give you even more insight into how beneficial a journal can be for you and your work. Altmetrics can be a valuable resource when determining where to publish your work. They are also a powerful tool for helping you know who is discussing your research and what they are saying about it, helping you enhance, increase, and further the impact and presence of your paper. Learn more

Each journal will provide instructions for authors on how to submit a paper, including the structure, formatting, word counts, and much more. Some journals may even provide a set of templates for manuscripts which can greatly help for structuring and formatting your papers and can be a helpful tool where available. Failure to comply with instructions for authors sits alongside aims and scope as the top reason articles are rejected from journals. Read more about how to ensure you comply with the journal’s requirements and what to expect when submitting to a journal.

If you need to include a cover letter with your submission, you should address the editor by formal name (e.g. Dear Professor Name---) and include the name of the journal. In the letter, explain why your article is suitable for that journal and how your paper will contribute to furthering its aims & scope. Pitch the value of your article, describing the main theme, the contribution your paper makes to existing knowledge, and its relationship to any relevant articles published in the journal. You should not repeat the abstract in the letter. Learn more about what to include in your cover letter.

Peer review is a process by which manuscripts are selected for publication in journals.

There are many different ways in which the process is conducted, but the core principle is that a submission is read by experts in the field, who provide comments to a senior editor to make a decision on whether to accept or reject the paper. The reviewers should comment on features such as the robustness of the methodology, and whether the research has been designed, conducted and analysed in a way which is coherent, valid and ethical.

The most common forms of peer review involve keeping identities of reviewers and/or authors secret, at least until the peer review process is over. These are known as Single Blind (where the author does not know the names of the reviewers), and Double Blind (where all author information is removed from a paper, and neither reviewers or authors can be identified).

Learn more about how the characteristics of the journal's peer review process can help you decide where to submit or how to prepare for the peer review process after submission.

It is common for the peer review process to keep the identities of reviewers and/or authors secret. This is known as either Single Blind or Double Blind.

Single Blind is where the author does not know the names of the reviewers, but the reviewers have access to the author's details.

Double Blind is where all author information is removed from a paper, and neither reviewers or authors can be identified

This may affect how you must format your paper on submission, as Double Blind journals often request the submission of a copy of the paper without any identifying information. Learn more

Trusted by researchers, scientists, students and government bodies in 158 countries across the globe, FSTA is the definitive way to search over fifty years of historic and emerging research in the sciences of food and health. Here’s a selection of commonly asked questions about the FSTA database. For more information on FSTA content and how to access it, take a look at our Solutions Hub

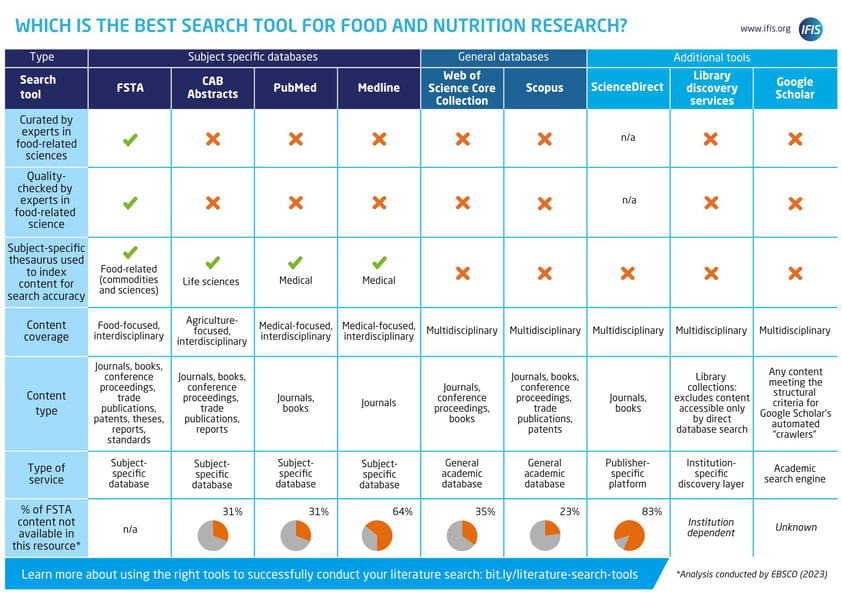

FSTA is the only database entirely devoted to research in this interdisciplinary field. We think it's the best! Take a look at our comparison chart to see all the reasons why.

FSTA contains over 1,700,000 high-quality records directly related to the sciences of food and health, including research from 82 countries and in 37 languages.

In addition to the core areas of food science, food technology and nutrition, FSTA includes relevant content across a host of related fields, including agriculture, microbiology, viticulture and oenology, biotechnology and much more.

For more information on FSTA content and how to access it, take a look at our Solutions Hub

1969 to the present- although a very small amount of content also predates 1969, the year the database was launched. New content is added on a weekly basis. Learn more about the history of FSTA and IFIS Publishing.

For more information on FSTA content and how to access it, take a look at our Solutions Hub

As part of our mission to fundamentally understand and best serve the information needs of the food community, we have established a small number of specialist advisory boards. If you are interested in being considered for membership, click on the boards below to find out more.

The FSTA Faculty Advisory Board is made up of prominent professors and researchers across the world, providing guidance on the coverage and content in FSTA and how to develop best practice in literature searching and literature reviews.

We established the FSTA Librarian Advisory Board in 2021. By bringing their insights into current and emerging issues facing academic librarians, board members will help advise IFIS about both FSTA and our information literacy initiatives.

The FSTA Student Advisory Board gives student representatives the chance to help us shape our offering, to make FSTA and our range of resources as useful as possible for our end users.

Through the establishment of the Nutritional Science collection, a Nutrition Advisory Board composed of Nutrition Society members have contributed their insights into current and emerging issues facing the nutrition community.

To help you get the best value out of your FSTA subscription, we have created a template description for you to use on your library website or subject guides. Please feel free to tailor the description of FSTA to highlight disciplines most relevant to your users.

We recommend adding FSTA to all relevant subject guides, not just food science and technology. Although food-focused, it is a very interdisciplinary database! See our full list of subject areas included here.

For more information on resource integration and promotional activities, take a look at our Solutions Hub

We have created a range of resources to help build awareness, drive usage, and provide training for the FSTA database, all available in our resources hub. All materials are free to download and include posters, flyers, graphics, and more! Take me to the resources hub

Social media is a great way to build awareness of library resources and drive usage. Our resources hub includes ideas to inspire your library social media posts, including downloadable graphics, logos, social media templates, and more. You can even customise these with the most relevant subject area and the url for the database on your own platform.

You can also download our logo to use when utilising and promoting our range of resources. Get the FSTA logo

For more information on resource integration and promotional activities, take a look at our Solutions Hub

5-9 Eden Street,

Kingston-Upon-Thames,

Surrey,

KT1 1BQ

© International Food Information Service (IFIS Publishing) operating as IFIS – All Rights Reserved | Charity Reg. No. 1068176 | Limited Company No. 3507902 | Designed by Blend