This blog post was informed by a talk at the Dubai International Food Safety Conference 2020, attended by Joanna Becker, IFIS' Senior Regulations and Compliance Executive.

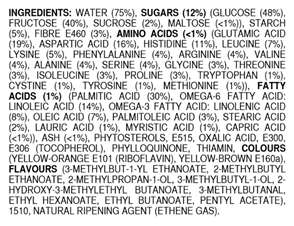

Below is a list of ingredients for a food product. As a consumer, if you saw these ingredients on the back of a food label, with all these chemical names, would you choose to purchase this item?

Image created by James Kennedy VCE Chemistry Lecturer at Melbourne University, Australia

Probably not?

You may be surprised to read that this is the exact chemical composition of a banana, not some highly processed, engineered food, full of additives.

In the age of social media and clean eating trends, the average consumer’s limited understanding of organic chemistry and food science has led to them shunning perceived “chemicals” in their foods. But when you break down a standard banana, a lot of the chemicals you would find in processed foods are also found in the all-natural banana.

This perception of what is good and what is healthy for us, as consumers, can lead to substantial challenges for the food industry. A generalised lack of food science knowledge and awareness can make it difficult for the food industry to use natural, organic compounds in their foods, or to even have them naturally present, without receiving a backlash from customers. It is clear that there needs to be more education when it comes to food labelling, what is classed as natural, and what is not, as this would allow consumers to make more informed choices about the foods they eat.

Eggs are currently very popular on platforms such as Instagram, through hashtags such as #eggsforlife and #eggsofinstagram. Many consumers see eggs as “natural” and “healthy”. However, most are unaware that eggs naturally contain formaldehyde - more commonly recognised as embalming fluid for human corpses. Therefore, should an egg not be classed as natural or healthy because of its naturally occurring chemical property?

Educating the consumer about what is in their food is essential, as consumer perception and trends can be very powerful. So much so, that the Hong Kong authorities decided to ban bromated vegetable oil in food products due to public protests, following a “leaked” video on social media about it being a chemical predominantly used as a flame retardant. This had huge implications for countries exporting products containing naturally occurring bromated vegetable oil to Hong Kong. The USDA (United States Department of Agriculture) had to negotiate with the Hong Kong authorities to allow foods containing bromated vegetable oil to be reconsidered, and the ban was eventually reversed.

Free whitepapers: Browse our collection of food science e-books

Similar hurdles are found in the sweetener industry, who face a constant struggle balancing scientific fact with consumer misinformation and perception of certain sweeteners. It can take years to establish acceptance of a new food product or additive, but it takes only one headline to destroy that trust. Should governments be banning substances based on the consumer’s thoughts and perceptions, which may not be backed by scientific facts? What is the point in having food scientists and toxicologists if we do not pay attention to their research, but potentially ban foods and additives due to consumer’s lack of understanding or knowledge?

Chemicals are often viewed in isolation when we should be seeing them as part of a bigger picture and considering the interaction of these chemicals together. An example of this is the French wine paradox. In general, wine and alcohol can lead to fatty liver disease, and the French population typically drink a lot of red wine and eat a very high-fat diet; however, they have some of the lowest rates of cardiovascular disease in Europe. If you looked at just the chemicals in wine, then it would be easy to see it as quite a potent mix of toxic chemicals. However, the chemical composition of red wine and its interaction with our bodies has been shown to have a protective effect in the French population against cardiovascular disease.

The same goes for coffee, which could be seen as having lots of “carcinogenic chemicals” in its chemical makeup; however, there are numerous studies which show the benefits of drinking coffee, including reduced insulin sensitivity. Depending on how many cups an individual drinks daily, coffee may even be protective against some cancers. Coffee contains chemicals such as acrylamide, which itself is known as a potent carcinogen, but coffee has been shown to also contain lots of antioxidant properties, such as chlorogenic acid. Therefore, we cannot look at foods via each singular chemical they contain. We need to understand the matrix and their biological interactions with us as humans, not purely brand the whole food product as carcinogenic because it may contain very low levels or traces of acrylamide.

Chemicals and additives in foods are constantly in the media, displayed through brash headlines which draw consumers eyes. From the examples above, it is clear that consumers need help understanding interactions between substances in foods. Clear and concise advice is required on the scientific evidence for the positive or negative effects of certain components, or at least, why something may be added to food.

Otherwise, consumers have the impossible task of wading though psuedo-news, over weighty media headlines, and unqualified “influencers” giving their opinions on certain aspects of foods and food groups. We, as consumers, face losing out on perfectly wholesome and nutritious foods by elevating misinformation and ignoring the scientific community, who are fundamentally the experts in the realms of food science, health and nutrition.

Photo by Matthew T Rader on UnsplashRelated posts:

Is food labelling the best communication tool for protecting consumers?