The market for botanical products has seen a steady increase over the last two decades. Botanicals and their preparations are widely consumed as food, food ingredients, food supplements, and herbal medicines. In 2017, the total retail sales of herbal supplements in the United States saw an increase of 8.5% from the previous year, valued at $8 billion. This increase was reported as the US’ strongest sales growth of herbal supplements in more than 15 years. In a similar trend, the EU sales of traditional and herbal products are expected to increase to over $8 billion in 2020. The cultural knowledge and practice of using various botanicals is becoming more widely known by other nations and cultures, increasing interest in their health effects.

In response to increasing demand, the botanicals industry is improving its capacity to produce different types of products. This is mostly backed up by trends in current research for exploring botanicals and their derivatives for health maintenance. Many botanicals are readily available in many forms, such as tablets, capsules, extracts, tea bags, and powders. These can be purchased through multiple channels, from health shop retailers to online stores and networks across the globe.

In the context of food, botanical products are viewed as natural sources of nutrition and flavour, and therefore safe for human consumption. However, there is increasing concern over the regular consumption of botanicals, especially new and emerging products such as dietary supplements, superfoods, and herbal medicines. This article reviews some of the likely risks related to the consumption of botanicals and their preparations, which are generally perceived as natural sources of chemicals with beneficial health effects.

Botanicals containing natural toxins

Despite being a widely accepted perception, the word “natural” does not necessarily mean safe. Of several thousand edible species of plants, many contain natural toxins proven to be harmful to human health. There are many research studies and official reports documenting human poisoning from botanicals with various degrees of adverse effects, from mild digestive discomfort to complete liver failure and some patients needing a liver transplant. Some of these chemicals are secondary metabolites produced in small quantities by plants as part of their defence against herbivores. These are unlikely to cause significant damage if digested accidentally or occasionally, but continuous exposure to these chemicals can have irreversible health consequences.

Figure 1 This is how herbs and species were traditionally sold as food ingredients across the world. The quantity is decided by customers or advised by shop owners for a specified use or mixed herb recipes. Antibes, France.

Pyrrolizidine Alkaloids (PAs), for example, are a group of heterocyclic organic compounds which occur in more than 6,000 plants, including more than 300 species and 13 families. Boraginaceae, Asteraceae and Fabaceae are the three main families known to contain different PAs and assumed to be hepatotoxic. For instance, comfrey teas (Symphytum spp.) were known for their medicinal properties and were marketed and consumed as herbal teas and medicines. They were removed from the US market in 2001 after they were banned in the UK and Australia because of their adverse effects. Contaminations of other botanicals with various types of PAs are also reported since many plants containing PAs are weed species. They naturally grow and are likely to be harvested with other plant species. The Codes of Practice (CoD) are developed by Tea and Herbal Infusions Europe (THIE) to prevent and reduce PA contamination of agricultural commodities produced as herbal teas and infusions to As Low As Reasonably Achievable (ALARA) levels.

Figure 2 some of the botanical products sold as food supplements in the UK.

Free whitepaper: Dietary Supplements - 'Self Prescribing a Legal Dose or Duped into Deficiency?'

Substitution, Adulteration and Misidentification

Quality controls of botanicals are not practised at the same level of sensitivity around the world, and therefore, there are continuous reports of various types of botanical products being adulterated or substituted with other species or materials. The misidentification of closely related species or similar-looking botanical products is more common than people may think. A large survey published in 2019 showed that of 5,597 commercial herbal products sold across 37 countries, 27% were adulterated when tested against their claimed identity from the labels. Herbal products from India and China showed 31% and 19% adulteration, respectively. Both countries are major suppliers of botanical products and are known for their well-established, traditional use of herbs and herbal medicines. This high percentage of adulteration indicates the likely risks consumers may be exposed to, considering the ease of access to a wide range of botanical products globally.

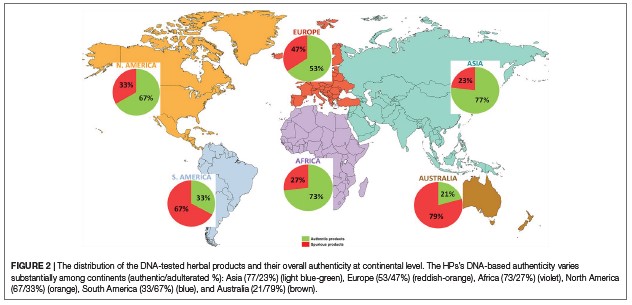

Figure 3 is taken from a global survey published in 2019 which reveals commercial herbal products are adulterated across the continents. Green: authentic Red: spurious.

Ichim, M. C. (2019). The DNA-based authentication of commercial herbal products reveals their globally widespread adulteration. Front Pharmacol. 2019.

Risks of over exposure and overdose

This ease of access coupled with new and emerging botanical products containing a concentrated level of their active constituents represents additional risks of exposure for consumers. Botanicals and their preparations, sold as food supplements in the form of tablets or extracts, can sometimes contain an active chemical at concentrations much higher than what is found in the original plant. There are various reports of adverse effects, including hepatotoxicity and liver failure, due to the consumption of green tea extracts (Camellia sinensis) mostly used for weight loss. In some cases, the products in question have been used in higher volumes or more frequently than usual. Although labelling for food supplements may state a recommended dose or guidance to not exceed this, they do not include details of the likely risks of overconsumption. It is worth noting that not all botanicals are assessed for their efficacy and safety, and their likely adverse effects on individuals remain unknown.

Figure 4 shows a food supplement label recommends consumers to not exceed the daily dose.

Safety assessment of botanical products and differences in required regulatory compliance

There are different approaches for evaluation and safety assessments of botanicals and their preparations, including the history of use, animal studies, tissue and cell culture, toxicological and carcinogenic studies. For most botanical products, relevant human clinical studies are lacking. The first-tier assessment is based on existing knowledge, including intended use, permissible levels, and methods of preparations. Under the EU laws, if there is sufficient knowledge about the traditional use of botanicals outside the EU, without documented evidence of their adverse effect, they can be permitted for sale in the EU market. Due to their complex nature and challenges in assessing their safety and efficacy, however, the use of some botanicals stay in debate and individual member states in the EU may stand against the use of certain products. On the other hand, permissible levels of use for the same botanicals vary, depending on the regulatory category they fall into. Both the gap in regulatory efforts and differences in levels of compliance can confuse consumers, who may well become the victims of their uncertain choices.

In the US, food supplements such as botanicals are not required to be assessed for safety and efficacy before marketing. In fact, in many cases, this information is not even available for some of the botanicals that are already in the market, unless their adverse effects come to light and they are recalled. The regulations for botanicals used as Traditional Herbal Medicines (THM) or herbal drugs are more stringent, and the United States Pharmacopoeia (USP) standardise quality control measures for herbal medicines. Similarly, in the UK, the Medicine and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) regulates and sets standards for herbal drugs sold in the UK market. In 2016, MHRA recalled several thousand packs of St John’s wort extract tablets from the UK market as a safety precaution, due to PAs contamination detected in some batches. St John’s wort (Hypericum perforarum) extract is used for treatments of anxiety, depression and insomnia. Seized products held Traditional Herbal Registrations (THR) certification, a market approval for safety and efficacy. This incidence showed that despite the rigour of quality controls, contamination in botanicals and their preparations are likely to go undetected due to content variation, likely caused by poor farming and harvesting practices.

Figure 5 some of the herbal products sold as traditional herbal medicines in the UK market.

“Safe use” rather than safe? A “big picture” safety is needed

More and more botanical products are produced and consumed each year due to widespread promotion of their beneficial health effects. At the same rate, concerns are raised about their frequent consumption and increasing reports of their adverse effects on consumers. Because of their complex nature, the safety assessment of botanical products is not straightforward, and current regulatory guidelines are continuously reviewed and toughened to protect consumers health. On the other hand, current approaches to the safety assessment of botanicals are thought to be limiting their use due to the lack of scientific evidence for their safety, including toxicological and carcinogenic studies. Accumulating relevant clinical information requires time for careful planning and conducting prioritised research of many botanicals. Meanwhile, it is important to increase consumer awareness of ‘safe use’ of botanical products by mediating a ‘big picture’ safety outlook, which considers risks versus benefits. Some may argue that these products were used traditionally by humans with little or no concerns for decades. It is worth noting that traditionally short-term or specified exposures were often practised. And therefore, it is not known whether a lifetime of frequent and regular exposure to botanical products is safe.

References:

Jennings, S. (2016). Quality of Botanical Preparations, specific recommendations for the manufacturing of botanical preparations, Including extracts as Food Supplements. European Botanical Forum, Food Supplements Europe. p 31.

Chugh, N. A., et al. (2018). "Integration of botanicals in contemporary medicine: roadblocks, checkpoints and go-ahead signals." Integr Med Res 7(2): 109-125.

Di Lorenzo, C., et al. (2015). "Adverse effects of plant food supplements and botanical preparations: a systematic review with critical evaluation of causality." British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 79(4): 578-592.

European Food Safety Authority, & EFSA Scientific Committee. (2009). Guidance on Safety assessment botanicals and botanical preparations intended for use as ingredients in food supplements. Efsa Journal, 7(9), 1249

Ichim, M. C. (2019). "The DNA-Based Authentication of Commercial Herbal Products Reveals Their Globally Widespread Adulteration." Front Pharmacol 10: 1227.

Mezzasalma V., et al. (2017). Poisonous or non-poisonous plants? DNA-based tools and applications for accurate identification. Int J Legal Med 131(1):1-19.

Schilter, B., et al. (2003). "Guidance for the safety assessment of botanicals and botanical preparations for use in food and food supplements." Food and Chemical Toxicology 41(12): 1625-1649.

THIE (2018). Code of Practice to Prevent and Reduce Pyrrolizidine Alkaloid Contamination in Raw Materials for Tea and Herbal Infusions. Hamburg, Germany, Tea and Herbal Infusions Europe. Issue 1, p 12.

Tyler Smitha, et al. (2018). Herbal Supplement Sales in US Increase 8.5% in 2017, Topping $8 Billion. Market Report, www.herbalgram.org. Issue 119.

Images: Lisa Hobbs on Unsplash, Paolo Bendandi on Unsplash and Mina Kalantar of IFIS Publishing.

-1.jpg)