Patents are rich and valuable information sources for food science and nutrition research, but searching for them can be a complicated business. Fortunately, the database FSTA is designed to make it easy for researchers to locate patents related to food and nutrition. From there it is a simple step to get the full text of the patent document itself.

The value of patents as research outputs

While most academic research in food and nutrition science is published in scholarly journals, research conducted in industry might be shared with the world only when its intellectual property can be protected, through patents. University researchers also sometimes patent methods and technologies. Searching for and reading patent documents can be the only way for researchers to get access to this information.

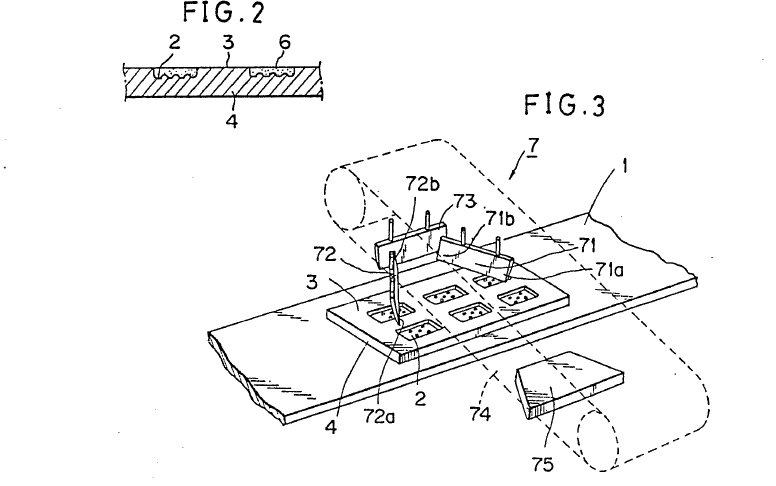

When we think of patents, we might picture drawings and diagrams. Often, though, patent applications are similar to research articles. The bulk of each is usually text organized into sections: abstract, background, detailed description of the invention, and claims of significance. A recently filed biodegradable film patent application ran to forty-six meticulously footnoted pages. To legally establish intellectual ownership, patent applications must describe an invention in enough detail that any person proficient in the field could replicate it. Patents are potentially more reproducible than studies described in the methods section of some scientific articles.

Why patent retrieval is complicated

Because patents publicly establish intellectual property the documents are published, in full, online. Theoretically, anyone can search for them, but to do so effectively requires specialized skills and knowledge.

What makes patent retrieval hard? The first complication is the sheer number filed each year with patent offices around the world. Also, each application can be published in multiple versions, pushing the number even higher. The versions are categorized by kind codes, and to make things even more complicated, these codes vary from country to country, and change over time as laws are updated.[1]

Furthermore, inventors have a propensity for writing up applications using complex, domain-specific jargon because it can help them establish the novelty of their work. Inventors sometimes use abstract, vague terms, too, to help extend their patent’s scope. All of this renders the traditional ways we tend search for online information not very effective for patent retrieval, or, as researchers investigating the problem wrote, “inappropriate or at least of limited applicability.”[2]

To effectively find patents, we need—at a minimum—to supplement traditional keyword searches with international patent classification (IPC) code searches. These codes pick up relevant documents keyword searches miss. For example, if we were searching for patents about masks, searching just for mask would fail to find “an otically supported polygonal barrier to respiratory pathways” or “a respiratory protection device comprising a central panel of filter media, and upper & lower panels with engageable extensions to form a chamber over the face.” Only an IPC code search would catch either of those.[3]

FSTA provides a straightforward solution for finding patents

In FSTA, searchers can effectively use traditional searching methods, because the FSTA editorial team has already done the specialized searching, and added to the database any and all food and nutrition related patents filed in fifteen European countries, the US, Japan, Canada, the European Patent Office, and under the international Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), which currently covers 153 countries. The editorial team does comprehensive IPC code searches, then uses kind codes to include first publications of patent applications, granted patents, and utility models, which are like patents but are less expensive to obtain, and offer a shorter tenure of protection.[4] FSTA contains more than 213,500 patent documents from 1969 onwards, and adds roughly 13,500 new patent records to the database each year.

Searching FSTA for patent records

Each patent record added to FSTA is indexed with thesaurus subject terms that capture the patent’s main elements whether or not the inventor used the exact word to capture the concept. A patent for “an otically supported polygonal barrier to respiratory pathways” would be indexed with the term mask, so a keyword search for mask would find that record, even though the inventor never used the word.

Also helpfully, because FSTA does not include any patents unrelated to food, the false hits searching problem is minimized. A false hit occurs when a search term has different meanings in different contexts. Searching for spirits patents in FSTA returns results about alcoholic beverages, and not about moods, fuel, or the supernatural.

After running a search in FSTA on a topic, filtering to see only the results which are patents is simple. It is also possible to search directly for an inventor or a patent assignee. All food and nutrition related patents assigned, for instance, to Unilever can be browsed by searching Unilever against the patent assignee field.[5]

Finding the full text of patents using the information found in FSTA

If, after reading the record’s title, abstract and subject terms, a patent looks useful, the next step is to get the full text. The FSTA record contains the key information needed: the publication number, title, and source and type of document (like French patent utility model application or United States patent). The record also includes other helpful information about the patent--its application number, the date or priority data information, the inventor, the assignee, the publication year, and language. With this information in hand, two free patent search interfaces usually enable a searcher to, relatively effortlessly, locate the documents. These are Google Patents and Espacenet.

Getting the full text with Google Patents

To check if Google Patents has the full text, copy and paste the patent’s title, inside quotation marks, into the simple search box. The quotation marks save time by taking a searcher directly to the right patent instead returning a long list of patents with the title’s words spread out randomly through the documents.

Searching by publication number also works, but spaces might need to be closed to pull up the correct document. For instance, the German patent “Printer cartridge with a chocolate dimension, in particular for 3D printing of a finished chocolate product” has a patent number DE 10 2018 217 443 A1, but Google Patents does not recognize it until the spaces are closed to DE102018217443 A1.

Sometimes Google Patents results will include a downloadable PDF version of a patent. With this German 3D chocolate printing patent, however, Google Patents only displays an HTML English version.

Getting the full text with Espacenet

Searching for the same patent in Espacenet, the European Patent Office’s search interface, gets even better results. There are two reasons for this. First, Epacenet’s records generally include the full original documents. Secondly, Espacenet’s records collate patent families, which means it links together the patent applications covering the same technical content that have been filed with different patent offices around the world.[6]

To search Espacenet, you can search the patent’s title (inside quotation marks) or the patent number (with spaces closed up). Search Espacenet for DE102018217443 A1 and you’ll see the 3D chocolate printing patent written up in German. Toggle to the Patent Family tab to see European and US patents for the same invention. Both these versions are written in English.[7] Select the “original document” for whichever version is in your preferred language. Next, click on the three dots in the upper right-hand corner of the screen, and you’ll see the option which enables you to download the full document.

Although it is hosted by the European Patent Office, Espacenet’s content is not restricted to European patents. A search for WO 2020/067381 A1, “Novel yeast derived from camellia growing in specific region” surfaces the documents for that patent filed with the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) and Japan’s patent office. In this case both original documents are in Japanese, but English translations of both the description and claims sections can be downloaded.

Going directly to a country’s patent office search

In the rare cases that Espacenet or Google Patents fail to retrieve a patent’s text, it is worth googling the patent office that issued the patent. This information is always listed in the FSTA record. Translate the patent office page if necessary and read it carefully to find the best way to proceed.

The benefits of starting patent searches with FSTA

If Google Patents and Espacenet work well most of the time to find the full text of patent documents, why not just search them directly to find food and nutrition related patent documents?

Remember that the overabundance of information makes it harder to locate the information you really need, as do the peculiar intricacies of patents themselves. Because the editorial team has searched by IPC codes, researchers using FSTA do not need to, nor do they need to go to multiple patent search interfaces to be confident they are searching a comprehensive pool of food-related patents.

Although patent searching is a highly skilled profession—patent agents, patent analysts, and patent attorneys all specialize in patent search—FSTA enables researchers not specialized in patent retrieval to efficiently locate and access the valuable research captured in these documents.

RELATED POSTS:

How to do effective literature searches

What is the difference between a systematic review and a systematic literature review?

FOOTNOTES

[1] An overview of kind codes can be found here: https://www.upcounsel.com/patent-kind-codes.

[2] Abbas, A., Zhang, L. and Khan, S. U. (2014) ‘A literature review on the state-of-the-art in patent analysis’, World Patent Information, 37, pp. 3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.wpi.2013.12.006.

[3]https://www.wipo.int/edocs/mdocs/mdocs/en/wipo_webinar_tisc_2020_9/wipo_webinar_tisc_2020_9_presentation.pdf

[5] An FSTA subscription on the Ovid or EBSCOhost platform also gives the option to search by patent number and patent priority, and EBSCOhost additionally offers a patent priority date field search.

[6] The Simple Family in Espacenet are patents covering the same technical content. The extended family content covers similar content, a distinction a searcher needs to be aware of. Patent families can be defined differently in different databases. See https://www.epo.org/searching-for-patents/helpful-resources/first-time-here/patent-families.html

[7] Espacenet offers a patent translate function for thirty-two different languages. Translation options appear on the upper right side of the screen.